|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

||||||||

BLOG

Thursday, October 17, 2024

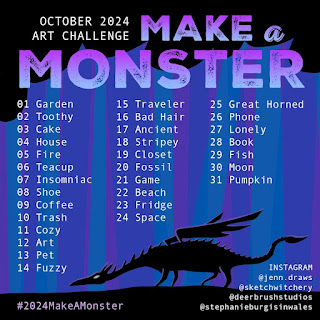

#2024MakeAMonster day 17: Ancient

Ancient

‘Wipe your shoes before you walk on my clean floor,’ Granny said. ‘Think I want your muck tracked over my house?’Since Grandpa died it had been duty visits. We went every Sunday, collecting Granny from church. Mum stayed behind in Granny’s house to cook the roast Granny insists on, and Granny tutted about Mum messing around in her kitchen, and on the drive she told Dad that he was letting us run wild and if he knew what was good for us he’d send us to church along with her.‘Kids need outdoor time, Mum,’ Dad said. He spoke with a kind of slow, rumbling authority, the way Grandpa used to talk, and Granny didn’t say anything back. She didn’t believe women should argue with men, which is why it was the rest of us who get the sharp edge of her tongue.She sat and tutted, though. She knew Dad took us to the woods, and she hadn’t forgiven them for being where Grandpa insisted on having his ashes scattered. It was a beautiful place, slopes of leaf-litter and the light spangling down through glowing green, and the stumps grown over with moss and mushrooms and towering ferns until they stood proud as citadels.‘Old growth forest,’ Grandpa used to say. He had a deep voice like Dad, a steady way of talking. He said few words, but they landed like a planted foot. ‘Nothing more living in the world, girls.’‘Think I want smuts and smears all over my good clean house?’ Granny said as we go in the door. ‘You children wipe your feet.’‘You children’ was me, Annie, and my twin sister Sally; ‘Annie-ly’, Grandpa used to call us, as if we were one creature. Granny would click her tongue, but we liked it. Grandpa understood that about us – that of course we weren’t a single person, but that there’d never been a time when we weren’t curled up together in each others’ lives, and that when teachers tried to separate us to ‘encourage independence’, it just meant we were sad about it. I loved Sally more than anyone, and at school they treated this like it meant there was something wrong with us, but Grandpa accepted it. ‘Branches on the tree together,’ he called us. ‘You go off, girls.’He loved the forest as much as we did. He and Dad had been the ones to take us there, though Mum came too. She was energetic and small, Mum, with short spiky hair and jeans and a love of hiking, and Granny considered her to ‘make no effort’, but she and Dad had met on a mountain trail and they loved to be out together. The only difference was that Mum went at it like she was so full of spirits that she needed to run them off; ‘my husky girl,’ Dad called her, like the sled dogs that need miles a day to keep cheerful, and when we went to the woods Mum would be up slopes and down them like she was surfing waves of earth. Dad and Grandpa, though, they went slow. Grandpa rested his hand on tree trunks as he walked by like he was stroking an animal. ‘Oak,’ he’d say, naming them. ‘Hawthorne. Rowan. Keeps the bad spirits away, rowan berries. Blood-red enough to scare ’em.’At church they’d told Granny that her husband was next door to a heathen, and that if he wasn’t careful he’d invite demons in.‘Nonsense,’ Grandpa said. ‘You want demons, you chatter about ’em. Dogs chase what runs. They don’t chase what stands.’We scattered his ashes in the old growth woods. Granny’s face was tight as a buttoned coat. ‘Heathen,’ she’d muttered. ‘Trouble.’‘It’s what he wanted,’ Dad said. Sally and I were crying, and Mum put an arm around each of us.After he was gone, Dad took us to the woods while Mum cooked for Granny. She didn’t get to clamber around with us any more, but she said she could put up with it if he’d mind us while she went for a long run in the morning. On Sundays when Granny had found too many things to say about her cooking, her clearing, her washing-up and her clothes, she’d go for another run in the evening too.But that was when Granny started to talk more about demons. There was a new preacher in her church, and he had a lot to say about them: about how this book or that celebrity or this sin invited in devilish spirits. Granny came back from church full of talk about it, nodding her head faster and faster as Dad said slowly, ‘Never mind, Mum. You’re safe enough.’It was Mum’s yoga that she started on then. The preacher had a lot to say about that. ‘Beguiled by deceivers,’ she’d say. ‘Devoting your body to false gods.’‘It’s just exercise, Mrs C,’ Mum said. ‘Helps me stay limber.’‘That’s what the demons would have you believe,’ said Granny. ‘Snares laid to trap the unwary.’‘I don’t see how God could mind that I stretch one way more than another,’ Mum said, tapping her fingers on the table; we could see she’d be out for a long run this evening. ‘Isn’t the body a temple?’‘A temple you profane!’ Granny said, getting more excited, and Dad said, ‘Now then, that’ll do. Let’s not have strife at our Sunday meal.’Back at home, Mum put on her running gear without a word; by the time she reached the door she was already bouncing on her toes.‘Have a good time, love,’ Dad said. ‘We’ll be fine, the girls and me.’‘I know she’s your mum, Tom,’ said Mum, ‘but she stretches my patience.’Dad kissed the top of her head. ‘Poor Liz,’ he said. ‘You’re a good woman. It’s good luck to care for the old.’Mum wasn’t mollified, but we knew she wouldn’t fight with Dad about it. He was her rock, she always said. ‘I was pretty lost when I met him,’ she told us once. ‘No family left of my own. Nowhere to call home, and no one to call home either, and that’s worse. Your dad gave me somewhere to put roots down.’ He’d warned her about Granny pretty early – ‘What’s true is true,’ he said – but we all knew that for a kiss and a compliment Mum would do pretty much anything for him.At Christmas Granny spent all day in church, and Mum had enough time that she could come to the woods with us for a couple of hours as well as cooking. The skies were white as the inside of an eggshell and little prickles of frost gilded the trees, and we tramped happily around, patting some of Grandpa’s favourite trunks. ‘Oak,’ Sally said, our way of wishing him happy Christmas, and I touched another and said, ‘Hazel.’ We almost felt the warmth through our gloves.Mum scurried under one of the trees where mistletoe hung bunched on the bare branches, pointing up. ‘Christmas baubles!’ she said, laughing, and Dad went over to kiss her. Sally and I pulled faces at each other – Mum and Dad being yuck – but it was comforting as well. Granddad had loved Mum and enjoyed seeing her in the forest. She couldn’t remember tree names the way we could, but he smiled and said she didn’t need to: she was a child of nature and didn’t need names to love it. ‘She’s lively as a robin, your Liz,’ he’d told Dad with approval. ‘A merry woman’s a blessing.’Dad picked a sprig of mistletoe up from the ground where it had fallen, tucked it behind Mum’s ear, kissed her again. ‘Posy for a pretty face,’ he said.Mum smiled bright as a Christmas star – but then her phone alarm chirped from her pocket and her face fell. ‘Better drop me back,’ she said. ‘She’ll be out of church soon and I’ll need to do the veg.’None of us wanted to leave; it was festivity out here, where the cold leaves crunched underfoot crackling like Christmas stockings and the bare branches feathered delicate against the sky. But Granny had been getting more and more agitated since this new preacher, and if we left her chatting in the lobby she’d only come home with worse ideas about how sinful everything was.It was the mistletoe that did it that Christmas. She wouldn’t let us over her threshold until we’d wiped and wiped and wiped every last trace of the old forest off our shoes, and then she sent us to wash our hands so we wouldn’t smear paganism over her furniture, and we were trying to keep our promise to Dad that we’d be patient and understand that without Grandpa to steady her, Granny was getting a little lost herself. But when she saw the mistletoe still tucked behind Mum’s ear, she shrieked.‘Bringing your druidry under my roof!’ she shouted.Mum jumped, and she jumped again as Granny reached out and snatched the leaves from her ear. She cupped her cheek as if Granny had slapped her.‘What are you doing, Mrs C?’ she demanded. Her face was sweaty from hours of cooking and her voice was not the forbearing tone Dad always coaxed from her. ‘After all this time cooking your dinner in your kitchen, all you can do is grab at me?’‘That’s right, make a show in front of the girls!’ Granny said, and we could see there were tears in her eyes. ‘You think I wouldn’t give anything to have the strength of my hands back? The strength of my body? But no, you have to run and leap and twist yourself into Godforsaken knots, and then bring your – your wickedness into my house and make mock of me! If I sold my soul to demons as you do, you think I couldn’t have your vigour? It’s a terrible bargain you make, Elizabeth, and if my Joseph were here it’d be a different thing, I’ll tell you that!’ She started to cry; she was shaking.‘Joseph loved greenery,’ Mum said, but Dad was stepping between them, towering over them both.‘Now then,’ he said, a voice like a put-down foot, ‘let’s have a little Christmas charity. We won’t quarrel.’Granny went silent, though she was still sparkling with angry tears, but Mum said, ‘You can say that if you like, Tom, but one of these days she’s going to go too far.’‘Not today,’ Dad said. ‘And Mum, you know Dad wouldn’t have liked bitter words. Let’s sit and eat and make peace.’‘I won’t eat with that devilish thing in my house,’ Granny said; it was as defiant as we’d ever seen her be with Dad.‘Fine,’ Mum said, and threw the mistletoe out of the window so hard we could hear it smack against Granny’s carefully-combed lawn.In the New Year Mum said to Dad that she seriously thought Granny was losing it. She couldn’t stop talking about everything being demonic, and she took offence at everything, and it was one thing to say it was a blessing to look after the elderly but Dad wasn’t the one being cursed for it at every turn.It was why she loved him, I think, that she could say things like that to Dad and he wouldn’t shout back. He looked angry for a second, but then he sat down, rubbed his face, thought about it. ‘I hear what you say, Lizzy,’ he said. ‘I know it’s hard on you.’Mum sat down in turn; it didn’t take much to remind her how much she wanted Dad to tend her. ‘She talks of Joseph like he was some fire-and-brimstone exorcist,’ she said. ‘She says if he was here he’d do something about all the demons she thinks I’m full of.’Dad sighed. ‘He had his own faith,’ he said. Nothing more than that. In his pocket he always kept a little carved wooden pebble, pale rowan that Granddad had carved him as a birthday present when he was young. He took it out now, rolled it between his fingers.‘Soon,’ Mum said, ‘she’s going to decide the whole forest is full of demons. She can’t lay off about the mistletoe to start with, and since then she’d been on and on about druids. She says they practiced human sacrifice, for pity’s sake.’Dad smiled then. ‘They did,’ he said. ‘Wasn’t their best idea, though.’‘Well, be that as it may, if she decides that old-growth woods are full of hobgoblins or whatever she thinks, she may start up on you for taking the girls there. And if she does that, well, I don’t know how much more blessed by caring for the old you want us to be before one of us tells her where to stick it.’A week later we got a call in the night. The police had found Granny in the churchyard, looking confused. She had handfuls of earth and she’d been trying to bury them in consecrated ground, she said, because they’d thrown her husband away in the wilderness and demons would get his soul.Dad went to collect her while we curled up with Mum on the sofa.‘Will they have to put Granny away?’ I asked. If Dad had been around to set an example I wouldn’t have sounded so hopeful.Mum kissed the top of my head, then Sally’s. ‘Your dad’ll try to avoid it,’ she said. She sighed. ‘And – and look, girls, I know Granny’s a cow to me most of the time, but I don’t want you to blame him for that. Your dad tries to do right by people, and that’s a good thing. That’s why he does right by us. Your Grandpa was the same. She always had a thing about evil spirits, but he talked like he knew of them, and he sounded so certain it settled her down. I don’t think we realised till he was gone how much she depended on that.’‘She’s not coming to live with us,’ Sally said, alarmed. We could see which way this might be heading.‘Good grief, I hope not,’ Mum said. ‘We’ll do everything we can to make sure she doesn’t, all right?’Dad said that Granny was getting rattled by this new preacher. She’d always been one to worry about things unseen, and he thought this man was a bad influence. He went to visit the man and told him politely that he thought some of his sermons weren’t good for the mental health of his flock, that Granny was old and anxious and hearing a bit more about the love of God and the protection of His children might do her some good.‘What did he say?’ Mum asked when he got home.Dad sighed. ‘Raised his hand over me and called for the demons of unbelief to release my soul.’Sally and I played in the woods by ourselves that Sunday; Dad said he trusted us to be sensible and Mum was right that it wasn’t fair she should be left to handle Granny all by herself. He’d be at the gate at twelve-thirty and he knew he could count on us to meet him there like good girls.The trees were still a lattice against cold white skies, nothing green and only the blackthorns showing thumb-tips of bud nestled tight against their branches. Sally and I eyed them with the hope of spring, but we didn’t touch them; Grandpa had said that some called it the wishing tree, and it was best not to trifle with it, for what we wished and what was best for us weren’t always the same thing.‘I won’t say I wish it,’ Sally said, ‘but Granny’s getting mean and it’s taking away Mum and Dad both. They’re no fun any more.’‘Dad says she’s getting old.’ I toed the leaf-litter around my boots; sometimes you could find hagstones.‘Grandpa was old.’We gazed around the woods, where Grandpa’s ashes had sifted into the ground.When Dad collected us we were chilled and thoughtful, but we weren’t prepared for Granny’s latest. As soon as we entered the door, wiping our boots as loud as we could before she could tell us off about it, she pointed to us and said, ‘Letting them do everything together! Arguing with their teachers about separating them! It’s twin-worship, that’s what it is, and that’s in every pagan and devil-worshipping cult the world ever had.’Mum wasn’t even angry; she looked shocked. ‘Mrs C,’ she said, ‘why don’t you sit down? Don’t upset yourself.’Sally and I reached for each others’ hands, and at that, Granny strode over to us. She grabbed Sally’s arm and tugged her hard; I screamed as Sally skidded to the floor.Dad looked up from his chair. ‘Now Mum,’ he said, louder than usual, ‘that’s enough.’Mum had run to Sally’s side, was trying to pick her up, but Granny wouldn’t let go. She was twisting her arm, raising her hand above Sally’s head and shouting something about releasing us from mortal bonds.‘Mummy!’ Sally wept, and I ran over to throw my arms around her. When I did, though, I screamed too. Granny’s skin was blazing hot; where she held Sally’s arm, and where she raised her other hand to push me, we burned and blistered.Dad stood up.He wasn’t a threatening man, Dad, though he was so big. Grandpa had been the same. They moved like trees: slow and steady, planting their feet with every step. It would have taken an axe to fell them.‘All right, Mum,’ he said, and his deep voice was very quiet, ‘I think enough is enough. You’ve gone and done it now, and now we’ve got to get you right again.’He reached into his pocket and drew out the hawthorn pebble Granddad had given him when he was a boy. Granny was still screaming, and it was easy to drop it in her mouth.As he covered her face, holding hard and saying, ‘Swallow it, Mum. It’ll do you good,’ I could see the edges of his skin darken, scorching like blackened wood. His face was twisted in pain, but he didn’t let go.‘Tom?’ Mum said. Her face was deathly white.‘It’s like Dad always said, Mum,’ Dad said through his teeth. Granny struggled against him. Fire budded and bloomed where she raised her hands. ‘You want something to come in, you talk of it too much.’ He lifted her up; she thrashed like a flame. ‘We should have got you a dog when he died. You’d have seen what he meant. That which hunts, it doesn’t chase what stands steady.’We didn’t see what happened to Granny out in the woods. Mum took us both to hospital; we had bad burns on our arms, which she told the nurse came from a cooking spill, and held our unhurt hands as we flinched and whimpered under the cleaning and the dressings.Dad was away for two days. Mum took us back to Granny’s house to look for him, but told us not to worry when they weren’t there. The doormat, where we’d wiped and wiped our feet free of the old-growth mulch, prickled with cool glints of daylight.So when Granny’s church burned down, it was a good none of us were anywhere near. Mum and we had doctors in A&E we could call as witnesses, and as to Dad – well, the police did ask because someone told them he’d quarrelled with the preacher. But several people said that they’d seen him walking in the woods. He was going from tree to tree, they said, apparently talking to himself, but he seemed quite all right. A lady walking her dog had spoken to him, and he said it was kind of her to ask, but not to worry: he was just doing some errands for his mother.Jenny Patel, that was the name of the dog-walker. We met at the police station and Mum invited her back for a cup of tea; she was nice, and said she always liked to meet other keen hikers. She and Mum took to going on shared jogs a few times a week. Her dog was having puppies, which Dad thought was marvellous; Jenny promised that when they were born, she’d give him first pick of them. He said his elderly mother had been suffering somewhat from loneliness, and a dog for company would do her good. Well, he said, ‘Let her see how not to start a chase,’ but Jenny had a bit of trouble with Dad’s accent and assumed he said something sensible.The church fire started around the altar, they said. Flames swallowed it down until there was nothing left but charred spicules, a little forest of brittle ash standing in a waste of soot.They never did find the preacher. Neighbours said they thought he might have taken to arson, as the congregation had been getting increasingly extreme, as they put it, and there had been shouting heard for days before. Then again, they thought he might have made enemies. He’d been accusing left and right in recent weeks, seeing demons everywhere.Dad wouldn’t let us or Mum go to Granny’s for a few more weeks. He said we’d done more than our share and we should let him take over for a while. But by next month he was smiling; he’d found her a new church, he said, and thought they’d be a good place for her. The preacher was a virtuous man, and listened sympathetically when Dad told him to be aware that Granny was ‘spiritually sensitive.’‘Told him it runs in the family,’ Dad said, putting his arms around us. ‘My dad did always see something in her. We’ll see how we go, though.’Granny still didn’t come to the woods with us. She said it made her miss her Joseph too much, and Polly, her new little puppy, found it easier in the park. But next time Mum made Sunday dinner and brought it through, she looked up from the table and said, ‘Thank you, Liz dear. It really is kind of you to make such an effort.’Mum looked at Dad.‘Why, you’re welcome, Mrs C,’ she said. ‘Nice of you to say so.’‘That’s all right, dear,’ Granny said. ‘We had a lovely performance in church just this morning – little Jan Porter sang, “How beautiful are the feet of them that preach the gospel of peace and bring glad tidings of good things.” Such an uplifting thought. Made me thing of you, Liz.’Mum almost tripped over the carpet as she brought the roast to the table, but she regained her feet and sat down without any further accidents.

Archives

July 2006 August 2006 September 2006 October 2006 November 2006 December 2006 January 2007 March 2007 May 2007 July 2007 October 2007 December 2007 January 2008 February 2008 March 2008 April 2008 May 2008 June 2008 July 2008 August 2008 September 2008 October 2008 November 2008 December 2008 January 2009 February 2009 March 2009 April 2009 May 2009 July 2009 August 2009 September 2009 October 2009 November 2009 December 2009 January 2010 February 2010 March 2010 April 2010 August 2010 September 2010 November 2010 January 2011 May 2011 June 2011 November 2011 December 2011 January 2012 February 2012 March 2012 April 2012 May 2012 June 2012 July 2012 August 2012 September 2012 October 2012 November 2012 December 2012 January 2013 March 2013 April 2013 May 2013 June 2013 July 2013 August 2013 September 2013 October 2013 March 2014 October 2021 June 2022 October 2024